Periodic Table With Roman Numerals

Roman numerals on stern of the ship Cutty Sark showing draught in feet. The numbers range from 13 to 22, from bottom to top.

Roman numerals are a numeral arrangement that originated in ancient Rome and remained the usual way of writing numbers throughout Europe well into the Late Middle Ages. Numbers in this system are represented by combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet. Modern manner uses 7 symbols, each with a fixed integer value:[1]

| Symbol | I | V | X | L | C | D | Chiliad |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | ane | 5 | ten | 50 | 100 | 500 | chiliad |

The use of Roman numerals continued long later the decline of the Roman Empire. From the 14th century on, Roman numerals began to be replaced by Standard arabic numerals; however, this process was gradual, and the use of Roman numerals persists in some applications to this day.

One place they are oftentimes seen is on clock faces. For instance, on the clock of Big Ben (designed in 1852), the hours from 1 to 12 are written every bit:

I, Two, III, 4, V, VI, Seven, Eight, IX, 10, XI, XII

The notations IV and Ix can be read every bit "1 less than v" (iv) and "ane less than ten" (9), although there is a tradition favouring representation of "iv" as "IIII" on Roman numeral clocks.[ii]

Other common uses include twelvemonth numbers on monuments and buildings and copyright dates on the title screens of movies and telly programs. MCM, signifying "a thousand, and a hundred less than another one thousand", means 1900, then 1912 is written MCMXII. For the years of this century, MM indicates 2000. The electric current year is MMXXII (2022).

Clarification

Roman numerals are essentially a decimal or "base ten" number system, but instead of identify value notation (in which place-keeping zeros enable a digit to stand for different powers of ten) the arrangement uses a ready of symbols with stock-still values, including "built in" powers of ten. Tally-similar combinations of these fixed symbols represent to the (placed) digits of Arabic numerals. This structure allows for significant flexibility in annotation, and many variant forms are attested.

In that location has never been an official or universally accepted standard for Roman numerals. Usage in ancient Rome varied profoundly and became thoroughly cluttered in medieval times. Even the postal service-renaissance restoration of a largely "classical" notation has failed to produce full consistency: variant forms are even dedicated by some modern writers as offering improved "flexibility".[3] On the other mitt, specially where a Roman numeral is considered a legally bounden expression of a number, equally in U.S. Copyright constabulary (where an "incorrect" or ambiguous numeral may invalidate a copyright claim, or affect the termination date of the copyright menstruum)[four] information technology is desirable to strictly follow the usual style described below.

Standard form

The following table displays how Roman numerals are ordinarily written:[5]

| Thousands | Hundreds | Tens | Units | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | C | X | I |

| two | MM | CC | Twenty | II |

| 3 | MMM | CCC | 30 | Three |

| 4 | CD | XL | Four | |

| five | D | Fifty | V | |

| 6 | DC | LX | VI | |

| vii | DCC | 70 | VII | |

| eight | DCCC | LXXX | 8 | |

| ix | CM | XC | IX |

The numerals for 4 (Four) and 9 (Nine) are written using "subtractive annotation",[half dozen] where the first symbol (I) is subtracted from the larger i (V, or X), thus avoiding the clumsier (IIII, and VIIII).[a] Subtractive notation is also used for 40 (40), 90 (XC), 400 (CD) and 900 (CM).[7] These are the simply subtractive forms in standard utilise.

A number containing two or more decimal digits is congenital by appending the Roman numeral equivalent for each, from highest to lowest, as in the following examples:

- 39 = 30 + IX = XXXIX .

- 246 = CC + XL + VI = CCXLVI .

- 789 = DCC + LXXX + IX = DCCLXXXIX .

- 2,421 = MM + CD + Xx + I = MMCDXXI .

Whatever missing identify (represented by a cypher in the identify-value equivalent) is omitted, equally in Latin (and English language) speech:

- 160 = C + LX = CLX

- 207 = CC + VII = CCVII

- 1,009 = M + IX = MIX

- ane,066 = M + Sixty + VI = MLXVI [8] [ix]

In practice, Roman numerals for numbers over m [b] are currently used mainly for twelvemonth numbers, as in these examples:

- 1776 = Grand + DCC + LXX + Half-dozen = MDCCLXXVI (the appointment written on the volume held past the Statue of Freedom).

- 1918 = M + CM + X + Viii = MCMXVIII (the first year of the Spanish flu pandemic)

- 1954 = M + CM + L + Four = MCMLIV (as in the trailer for the movie The Concluding Fourth dimension I Saw Paris)[four]

- 2014 = MM + X + Four = MMXIV (the year of the games of the XXII (22nd) Olympic Winter Games (in Sochi, Russia))

The largest number that can be represented in this annotation is 3,999 ( MMMCMXCIX ), only since the largest Roman numeral likely to exist required today is MMXXII (the current twelvemonth) there is no practical demand for larger Roman numerals. Prior to the introduction of Arabic numerals in the West, ancient and medieval users of the organization used various means to write larger numbers; see large numbers below.

Other forms

Forms exist that vary in ane way or some other from the general standard represented above.

Other additive forms

While subtractive annotation for 4, twoscore and 400 (Four, XL and CD) has been the usual form since Roman times, additive notation to represent these numbers (IIII, XXXX and CCCC)[10] continued to exist used, including in compound numbers like XXIIII,[xi] LXXIIII,[12] and CCCCLXXXX.[thirteen] The additive forms for 9, 90, and 900 (VIIII,[10] LXXXX,[14] and DCCCC [15]) take likewise been used, although less often.

The 2 conventions could be mixed in the same document or inscription, even in the aforementioned numeral. For example, on the numbered gates to the Colosseum, IIII is systematically used instead of Four, but subtractive annotation is used for Forty; consequently, gate 44 is labelled XLIIII.[16] [17]

Modern clock faces that use Roman numerals notwithstanding very often use IIII for iv o'clock but Ix for nine o'clock, a practice that goes back to very early clocks such equally the Wells Cathedral clock of the belatedly 14th century.[18] [19] [twenty] However, this is far from universal: for example, the clock on the Palace of Westminster tower (unremarkably known as Large Ben) uses a subtractive IV for 4 o'clock.[19] The number IIII is referred as le quatre d'horloger (French for the clockmaker'south iv).[ commendation needed ] Information technology makes the clock quadrant more balanced and esthetically pleasant, equally four number comprise I, iv numbers contain V and iv numbers contain 10.[ citation needed ]

Isaac Asimov once mentioned an "interesting theory" that Romans avoided using Iv because it was the initial letters of IVPITER , the Latin spelling of Jupiter, and might take seemed impious.[21] He did non say whose theory it was.

The yr number on Admiralty Arch, London. The year 1910 is rendered as

MDCCCCX, rather than the more usual

MCMX

Several monumental inscriptions created in the early 20th century utilize variant forms for "1900" (normally written MCM). These vary from MDCCCCX for 1910 as seen on Admiralty Arch, London, to the more than unusual, if not unique MDCDIII for 1903, on the north entrance to the Saint Louis Art Museum.[22]

Especially on tombstones and other funerary inscriptions 5 and fifty have been occasionally written IIIII and XXXXX instead of V and Fifty, and in that location are instances such every bit IIIIII and XXXXXX rather than Half dozen or LX.[23] [24]

Other subtractive forms

There is a common belief that any smaller digit placed to the left of a larger digit is subtracted from the full, and that by clever choices a long Roman numeral can be "compressed". The best known example of this is the ROMAN() function in Microsoft Excel, which tin can turn 499 into CDXCIX, LDVLIV, XDIX, VDIV, or ID depending on the "Form" setting.[25] There is no indication this is annihilation other than an invention by the programmer, and the universal-subtraction belief may exist a result of modern users trying to rationalize the syntax of Roman numerals.

Epitaph of centurion Marcus Caelius, showing "

XIIX"

There is, however, some historic use of subtractive note other than that described in the above "standard": in particular IIIXX for 17,[26] IIXX for xviii,[27] IIIC for 97,[28] IIC for 98,[29] [30] and IC for 99.[31] A possible explanation is that the word for 18 in Latin is duodeviginti , literally "two from 20", 98 is duodecentum (two from hundred), and 99 is undecentum (one from hundred).[32] However, the explanation does not seem to use to IIIXX and IIIC, since the Latin words for 17 and 97 were septendecim (seven ten) and nonaginta septem (ninety seven), respectively.

At that place are multiple examples of IIX being used for 8. There does not seem to be a linguistic explanation for this utilise, although it is i stroke shorter than VIII. XIIX was used past officers of the XVIII Roman Legion to write their number.[33] [34] The notation appears prominently on the cenotaph of their senior centurion Marcus Caelius (c. 45 BC – 9 Ad). On the publicly displayed official Roman calendars known as Fasti, XIIX is used for the eighteen days to the next Kalends, and XXIIX for the 28 days in February. The latter tin can be seen on the sole extant pre-Julian agenda, the Fasti Antiates Maiores.[35]

Rare variants

While irregular subtractive and condiment note has been used at least occasionally throughout history, some Roman numerals take been observed in documents and inscriptions that do not fit either arrangement. Some of these variants exercise not seem to have been used outside specific contexts, and may have been regarded as errors fifty-fifty by contemporaries.

Padlock used on the north gate of the Irish town of Athlone. "1613" in the appointment is rendered

XVIXIII, (literally "16, 13") instead of

MDCXIII.

- IIXX was how people associated with the XXII Roman Legion used to write their number. The practice may have been due to a common style to say "twenty-2d" in Latin, namely duo et vice(northward)sima (literally "two and twentieth") rather than the "regular" vice(n)sima secunda (twenty second).[36] Apparently, at least 1 ancient stonecutter mistakenly idea that the IIXX of "22nd Legion" stood for eighteen, and "corrected" information technology to XVIII.[36]

![]()

- In that location are some examples of year numbers after 1000 written as ii Roman numerals i–99, due east.g. 1613 as XVIXIII, corresponding to the common reading "sixteen thirteen" of such year numbers in English language, or 1519 as XVCXIX equally in French quinze-cent-dix-neuf (fifteen-hundred and nineteen), and like readings in other languages.[38]

- In some French texts from the 15th century and later one finds constructions like IIIITwentyXIX for 99, reflecting the French reading of that number as quatre-vingt-dix-neuf (four-score and nineteen).[38] Similarly, in some English documents i finds, for example, 77 written as "iiixxxvii" (which could be read "three-score and seventeen").[39]

- Another medieval bookkeeping text from 1301 renders numbers similar thirteen,573 as " Xiii. M. 5. C. III. Xx. 13 ", that is, "xiii×1000 + five×100 + 3×20 + 13".[40]

- Other numerals that do not fit the usual patterns – such as VXL for 45, instead of the usual XLV — may be due to scribal errors, or the author'south lack of familiarity with the organisation, rather than existence 18-carat variant usage.

Not-numeric combinations

Every bit Roman numerals are composed of ordinary alphabetic characters, there may sometimes be confusion with other uses of the aforementioned letters. For example, "30" and "XL" have other connotations in addition to their values every bit Roman numerals, while "IXL" by and large is a gramogram of "I excel", and is in any instance not an unambiguous Roman numeral.[41]

Nothing

Equally a non-positional numeral system, Roman numerals have no "place-keeping" zeros. Furthermore, the system as used by the Romans lacked a numeral for the number zero itself (that is, what remains after 1 is subtracted from ane). The word nulla (the Latin word pregnant "none") was used to represent 0, although the earliest attested instances are medieval. For instance Dionysius Exiguus used nulla alongside Roman numerals in a manuscript from 525 Advertizement.[42] [43] About 725, Bede or one of his colleagues used the letter Northward, the initial of nulla or of nihil (the Latin word for "nothing") for 0, in a tabular array of epacts, all written in Roman numerals.[44]

The utilise of Northward to indicate "none" long survived in the celebrated apothecaries' organisation of measurement: used well into the 20th century to designate quantities in pharmaceutical prescriptions.[45]

Fractions

A triens coin ( i⁄3 or

iv⁄12 of an as ). Note the four dots (····) indicating its value.

A semis money (

1⁄2 or

half dozen⁄12 of an every bit ). Note the

S indicating its value.

The base "Roman fraction" is S, indicating i⁄ii . The employ of S (as in VIIS to indicate seven 1⁄2 ) is attested in some ancient inscriptions[46] and also in the now rare apothecaries' system (normally in the form SS):[45] but while Roman numerals for whole numbers are substantially decimal S does not stand for to 5⁄10 , as i might await, simply 6⁄12 .

The Romans used a duodecimal rather than a decimal system for fractions, as the divisibility of twelve (12 = 22 × 3) makes it easier to handle the common fractions of 1⁄three and ane⁄4 than does a organization based on x (10 = two × 5). Annotation for fractions other than 1⁄2 is mainly found on surviving Roman coins, many of which had values that were duodecimal fractions of the unit as . Fractions less than 1⁄two are indicated by a dot (·) for each uncia "12th", the source of the English words inch and ounce; dots are repeated for fractions upward to 5 twelfths. Vi twelfths (1 half), is Due south for semis "half". Uncia dots were added to S for fractions from vii to eleven twelfths, just as tallies were added to Five for whole numbers from 6 to ix.[47] The arrangement of the dots was variable and not necessarily linear. Five dots arranged similar (⁙) (as on the face of a die) are known as a quincunx, from the proper name of the Roman fraction/coin. The Latin words sextans and quadrans are the source of the English words sextant and quadrant.

Each fraction from 1⁄12 to 12⁄12 had a proper name in Roman times; these corresponded to the names of the related coins:

| Fraction | Roman numeral | Proper name (nominative and genitive) | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| one⁄12 | · | Uncia, unciae | "Ounce" |

| 2⁄12 = 1⁄half dozen | ·· or : | Sextans, sextantis | "Sixth" |

| three⁄12 = one⁄4 | ··· or ∴ | Quadrans, quadrantis | "Quarter" |

| 4⁄12 = i⁄iii | ···· or ∷ | Triens, trientis | "Third" |

| v⁄12 | ····· or ⁙ | Quincunx, quincuncis | "Five-ounce" (quinque unciae → quincunx) |

| 6⁄12 = ane⁄2 | South | Semis, semissis | "One-half" |

| 7⁄12 | S · | Septunx, septuncis | "Vii-ounce" (septem unciae → septunx) |

| 8⁄12 = 2⁄three | S ·· or S : | Bes, bessis | "Twice" (as in "twice a tertiary") |

| nine⁄12 = 3⁄iv | S ··· or S ∴ | Dodrans, dodrantis or nonuncium, nonuncii | "Less a quarter" (de-quadrans → dodrans) or "ninth ounce" (nona uncia → nonuncium) |

| ten⁄12 = 5⁄vi | S ···· or S ∷ | Dextans, dextantis or decunx, decuncis | "Less a sixth" (de-sextans → dextans) or "x ounces" (decem unciae → decunx) |

| eleven⁄12 | S ····· or Southward ⁙ | Deunx, deuncis | "Less an ounce" (de-uncia → deunx) |

| 12⁄12 = ane | I | As, assis | "Unit" |

Other Roman fractional notations included the following:

| Fraction | Roman numeral | Name (nominative and genitive) | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| one⁄1728 =12−three | 𐆕 | Siliqua, siliquae | |

| 1⁄288 | ℈ | Scripulum, scripuli | "scruple" |

| 1⁄144 =12−2 | 𐆔 | Dimidia sextula, dimidiae sextulae | "half a sextula" |

| 1⁄72 | 𐆓 | Sextula, sextulae | " 1⁄6 of an uncia" |

| 1⁄48 | Ↄ | Sicilicus, sicilici | |

| 1⁄36 | 𐆓𐆓 | Binae sextulae, binarum sextularum | "two sextulas" ( duella, duellae ) |

| i⁄24 | Σ or 𐆒 or Є | Semuncia, semunciae | " 1⁄2 uncia" (semi- + uncia) |

| 1⁄viii | Σ· or 𐆒· or Є· | Sescuncia, sescunciae | "1+ 1⁄2 uncias" (sesqui- + uncia) |

Large numbers

During the centuries that Roman numerals remained the standard fashion of writing numbers throughout Europe, at that place were various extensions to the arrangement designed to indicate larger numbers, none of which were ever standardised.

Apostrophus

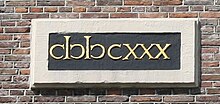

"1630" on the Westerkerk in Amsterdam. "

Yard" and "

D" are given archaic "apostrophus" form.

One of these was the apostrophus,[48] in which 500 was written as IↃ, while 1,000 was written equally CIↃ.[21] This is a system of encasing numbers to denote thousands (imagine the Cs and Ↄsouth equally parentheses), which has its origins in Etruscan numeral usage. The IↃ and CIↃ used to represent 500 and 1,000 most likely preceded, and afterward influenced, the adoption of "D" and "Yard" in conventional Roman numerals.

Each boosted set of C and Ↄ surrounding CIↃ raises the value by a factor of ten: CCIↃↃ represents 10,000 and CCCIↃↃↃ represents 100,000. Similarly, each additional Ↄ to the right of IↃ raises the value past a factor of ten: IↃↃ represents v,000 and IↃↃↃ represents 50,000. Numerals larger than CCCIↃↃↃ do not occur.[49]

Page from a 16th-century manual, showing a mixture of apostrophus and vinculum numbers (see in particular the ways of writing 10,000).

Sometimes CIↃ was reduced to ↀ for 1,000. John Wallis is oftentimes credited for introducing the symbol for infinity (modernistic ∞), and one conjecture is that he based it on this usage, since 1,000 was hyperbolically used to represent very big numbers. Similarly, IↃↃ for 5,000 was reduced to ↁ; CCIↃↃ for ten,000 to ↂ; IↃↃↃ for 50,000 to ↇ (ↇ); and CCCIↃↃↃ (ↈ) for 100,000 to ↈ. [fifty]

Vinculum

Another system was the vinculum, in which conventional Roman numerals were multiplied by 1,000 by calculation a "bar" or "overline".[50] It was a common alternative to the apostrophic ↀ during the Majestic era: both systems were in simultaneous use around the Roman world (G for 'grand' was non in employ until the Medieval flow).[51] [52] The employ of vinculum for multiples of 1,000 can be observed, for example, on the milestones erected by Roman soldiers along the Antonine Wall in the mid-2nd century AD.[53] The vinculum for marking one,000s continued in use in the Middle Ages, though it became known more usually as titulus.[54]

Some modern sources describe the vinculum as if it were a part of the current "standard".[55] However, this is purely hypothetical, since no common modern usage requires numbers larger than the current year (MMXXII). Still, here are some examples, to give an thought of how information technology might exist used:

- Iv = 4,000

- IV DCXXVII = iv,627

- XXV = 25,000

- XXV CDLIX = 25,459

Another inconsistent medieval usage was the improver of vertical lines (or brackets) before and after the numeral to multiply it by 10 (or 100): thus M for 10,000 as an alternative form for Ten . In combination with the overline the bracketed forms might exist used to heighten the multiplier to (say) 10 (or one hundred) thousand, thus:

- 8 for 80,000 (or 800,000)

- Twenty for 200,000 (or 2,000,000)

Apply of Roman numeral "

I" (with exaggerated serifs) contrasting with the upper case letter "I".

This use of lines is distinct from the custom, one time very common, of calculation both underline and overline (or very large serifs) to a Roman numeral, simply to brand information technology clear that it is a number, e.one thousand. ![]() for 1967. There is some scope for defoliation when an overline is meant to announce multiples of 1,000, and when not. The Greeks and Romans often overlined messages acting equally numerals to highlight them from the general body of the text, without any numerical significance. This stylistic convention was, for example, also in use in the inscriptions of the Antonine Wall,[56] and the reader is required to decipher the intended pregnant of the overline from the context.

for 1967. There is some scope for defoliation when an overline is meant to announce multiples of 1,000, and when not. The Greeks and Romans often overlined messages acting equally numerals to highlight them from the general body of the text, without any numerical significance. This stylistic convention was, for example, also in use in the inscriptions of the Antonine Wall,[56] and the reader is required to decipher the intended pregnant of the overline from the context.

Origin

The system is closely associated with the ancient city-country of Rome and the Empire that it created. However, due to the scarcity of surviving examples, the origins of the system are obscure and there are several competing theories, all largely conjectural.

Etruscan numerals

Rome was founded sometime between 850 and 750 BC. At the time, the region was inhabited by various populations of which the Etruscans were the almost advanced. The ancient Romans themselves admitted that the basis of much of their civilization was Etruscan. Rome itself was located side by side to the southern edge of the Etruscan domain, which covered a big office of north-central Italy.

The Roman numerals, in particular, are directly derived from the Etruscan number symbols: ⟨𐌠⟩, ⟨𐌡⟩, ⟨𐌢⟩, ⟨𐌣⟩, and ⟨𐌟⟩ for one, 5, x, l, and 100 (They had more symbols for larger numbers, just it is unknown which symbol represents which number). As in the basic Roman system, the Etruscans wrote the symbols that added to the desired number, from higher to lower value. Thus the number 87, for instance, would be written l + ten + 10 + 10 + 5 + 1 + 1 = 𐌣𐌢𐌢𐌢𐌡𐌠𐌠 (this would announced as 𐌠𐌠𐌡𐌢𐌢𐌢𐌣 since Etruscan was written from right to left.)[57]

The symbols ⟨𐌠⟩ and ⟨𐌡⟩ resembled letters of the Etruscan alphabet, but ⟨𐌢⟩, ⟨𐌣⟩, and ⟨𐌟⟩ did non. The Etruscans used the subtractive notation, too, but not like the Romans. They wrote 17, 18, and 19 as 𐌠𐌠𐌠𐌢𐌢, 𐌠𐌠𐌢𐌢, and 𐌠𐌢𐌢, mirroring the manner they spoke those numbers ("3 from twenty", etc.); and similarly for 27, 28, 29, 37, 38, etc. However they did non write 𐌠𐌡 for iv (nor 𐌢𐌣 for 40), and wrote 𐌡𐌠𐌠, 𐌡𐌠𐌠𐌠 and 𐌡𐌠𐌠𐌠𐌠 for 7, eight, and ix, respectively.[57]

Early Roman numerals

The early Roman numerals for 1, 10, and 100 were the Etruscan ones: ⟨𐌠⟩, ⟨𐌢⟩, and ⟨𐌟⟩. The symbols for 5 and 50 changed from ⟨𐌡⟩ and ⟨𐌣⟩ to ⟨V⟩ and ⟨ↆ⟩ at some point. The latter had flattened to ⟨⊥⟩ (an inverted T) past the time of Augustus, and soon subsequently became identified with the graphically similar letter ⟨L⟩.[49]

The symbol for 100 was written variously as ⟨𐌟⟩ or ⟨ↃIC⟩, was so abbreviated to ⟨Ↄ⟩ or ⟨C⟩, with ⟨C⟩ (which matched the Latin alphabetic character C) finally winning out. It might have helped that C was the initial letter of CENTUM, Latin for "hundred".

The numbers 500 and 1000 were denoted past V or X overlaid with a box or circle. Thus 500 was similar a Ↄ superimposed on a Þ . It became D or Ð past the time of Augustus, under the graphic influence of the letter of the alphabet D. Information technology was later identified as the letter of the alphabet D; an alternative symbol for "thousand" was a CIↃ, and half of a m or "v hundred" is the correct half of the symbol, IↃ, and this may accept been converted into D.[21]

The notation for thou was a circled or boxed 10: Ⓧ, ⊗, ⊕, and by Augustinian times was partially identified with the Greek letter Φ phi. Over time, the symbol changed to Ψ and ↀ. The latter symbol further evolved into ∞, then ⋈, and somewhen changed to Thousand under the influence of the Latin word mille "thousand".[49]

According to Paul Kayser, the basic numerical symbols were I, X, C and Φ (or ⊕) and the intermediate ones were derived by taking half of those (half an 10 is V, half a C is L and half a Φ/⊕ is D).[58]

Archway to section

LII (52) of the Colosseum, with numerals all the same visible

Classical Roman numerals

The Colosseum was constructed in Rome in CE 72–80,[59] and while the original perimeter wall has largely disappeared, the numbered entrances from XXIII (23) to LIIII (54) survive,[60] to demonstrate that in Imperial times Roman numerals had already assumed their classical form: every bit largely standardised in current utilise. The most obvious bibelot (a common i that persisted for centuries) is the inconsistent use of subtractive notation - while XL is used for 40, Four is avoided in favour of IIII: in fact gate 44 is labelled XLIIII.

Use in the Middle Ages and Renaissance

Lower case, or minuscule, letters were developed in the Middle Ages, well after the demise of the Western Roman Empire, and since that fourth dimension lower-case versions of Roman numbers have also been commonly used: i, ii, 3, iv, and so on.

![]()

13th century example of

iiij.

Since the Middle Ages, a "j" has sometimes been substituted for the final "i" of a "lower-case" Roman numeral, such every bit "iij" for 3 or "vij" for seven. This "j" can be considered a swash variant of "i". Into the early 20th century, the use of a final "j" was even so sometimes used in medical prescriptions to forestall tampering with or misinterpretation of a number afterward it was written.[61]

Numerals in documents and inscriptions from the Middle Ages sometimes include boosted symbols, which today are chosen "medieval Roman numerals". Some simply substitute another letter for the standard ane (such as "A" for "V", or "Q" for "D"), while others serve as abbreviations for compound numerals ("O" for "XI", or "F" for "Forty"). Although they are still listed today in some dictionaries, they are long out of use.[62]

| Number | Medieval abridgement | Notes and etymology |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | A | Resembles an upside-down V. As well said to equal 500. |

| 6 | ↅ | Either from a ligature of 6, or from digamma (ϛ), the Greek numeral 6 (sometimes conflated with the στ ligature).[49] |

| 7 | Southward, Z | Presumed abbreviation of septem , Latin for 7. |

| 9.5 | X̷ | Scribal abridgement, an x with a slash through information technology. Too, IX̷ represented eight.5 |

| 11 | O | Presumed abbreviation of onze , French for 11. |

| 40 | F | Presumed abbreviation of English 40. |

| lxx | Southward | Likewise could correspond 7, with the same derivation. |

| lxxx | R | |

| ninety | N | Presumed abbreviation of nonaginta , Latin for 90. (Ambiguous with N for "nothing" (nihil)). |

| 150 | Y | Possibly derived from the lowercase y'due south shape. |

| 151 | K | Unusual, origin unknown; also said to stand up for 250.[63] |

| 160 | T | Possibly derived from Greek tetra, as 4 × twoscore = 160. |

| 200 | H | Could also stand up for two (see likewise 𐆙, the symbol for the dupondius). From a barring of two I's. |

| 250 | Due east | |

| 300 | B | |

| 400 | P, G | |

| 500 | Q | Redundant with D; abbreviates quingenti , Latin for 500. Also sometimes used for 500,000.[64] |

| 800 | Ω | Borrowed from Gothic. |

| 900 | ϡ | Borrowed from Gothic. |

| 2000 | Z |

Chronograms, messages with dates encoded into them, were pop during the Renaissance era. The chronogram would be a phrase containing the letters I, V, 10, L, C, D, and M. By putting these letters together, the reader would obtain a number, usually indicating a item year.

Modern use

Past the 11th century, Arabic numerals had been introduced into Europe from al-Andalus, by style of Arab traders and arithmetic treatises. Roman numerals, however, proved very persistent, remaining in mutual utilize in the West well into the 14th and 15th centuries, fifty-fifty in accounting and other business records (where the actual calculations would have been made using an abacus). Replacement by their more user-friendly "Standard arabic" equivalents was quite gradual, and Roman numerals are however used today in sure contexts. A few examples of their current use are:

Castilian Existent using

IIII instead of

4 as regnal number of Charles

Iv of Espana.

- Names of monarchs and popes, e.1000. Elizabeth Two of the United Kingdom, Pope Benedict XVI. These are referred to as regnal numbers and are normally read as ordinals; eastward.g. II is pronounced "the second". This tradition began in Europe sporadically in the Heart Ages, gaining widespread utilize in England during the reign of Henry Viii. Previously, the monarch was non known by numeral but past an epithet such as Edward the Confessor. Some monarchs (e.g. Charles 4 of Spain and Louis XIV of French republic) seem to have preferred the use of IIII instead of IV on their coinage (encounter illustration).

- Generational suffixes, particularly in the U.South., for people sharing the same name across generations, for instance William Howard Taft IV. These are as well usually read as ordinals.

- In the French Republican Calendar, initiated during the French Revolution, years were numbered by Roman numerals – from the year I (1792) when this calendar was introduced to the twelvemonth XIV (1805) when information technology was abandoned.

- The year of production of films, television shows and other works of art within the piece of work itself. Outside reference to the work will use regular Arabic numerals.

The year of construction of the Cambridge Public Library, (USA) 1888, displayed in "standard" Roman numerals on its facade.

- Hour marks on timepieces. In this context, 4 is oft written IIII.

- The year of construction on building façades and cornerstones.

- Page numbering of prefaces and introductions of books, and sometimes of appendices and annexes, besides.

- Book volume and chapter numbers, besides as the several acts inside a play (eastward.yard. Human action iii, Scene two).

- Sequels to some films, video games, and other works (as in Rocky Ii, Grand Theft Auto V).

- Outlines that apply numbers to show hierarchical relationships.

- Occurrences of a recurring m event, for instance:

- The Summer and Winter Olympic Games (east.grand. the XXI Olympic Winter Games; the Games of the XXX Olympiad).

- The Super Basin, the annual championship game of the National Football game League (e.one thousand. Super Bowl XLII; Super Bowl l was a 1-time exception[65]).

- WrestleMania, the almanac professional wrestling event for the WWE (e.k. WrestleMania XXX). This usage has as well been inconsistent.

Specific disciplines

In astronautics, United States rocket model variants are sometimes designated by Roman numerals, due east.chiliad. Titan I, Titan II, Titan Iii, Saturn I, Saturn 5.

In astronomy, the natural satellites or "moons" of the planets are traditionally designated by capital Roman numerals appended to the planet'south proper noun. For example, Titan's designation is Saturn Six.

In chemistry, Roman numerals are often used to denote the groups of the periodic tabular array. They are also used in the IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry, for the oxidation number of cations which tin take on several different positive charges. They are also used for naming phases of polymorphic crystals, such every bit water ice.

In education, school grades (in the sense of year-groups rather than test scores) are sometimes referred to by a Roman numeral; for example, "grade Ix" is sometimes seen for "grade ix".

In entomology, the broods of the thirteen and seventeen year journal cicadas are identified by Roman numerals.

In graphic design stylised Roman numerals may represent numeric values.

In police force, Roman numerals are commonly used to help organize legal codes equally part of an alphanumeric outline.

In advanced mathematics (including trigonometry, statistics, and calculus), when a graph includes negative numbers, its quadrants are named using I, 2, Three, and Four. These quadrant names signify positive numbers on both axes, negative numbers on the X centrality, negative numbers on both axes, and negative numbers on the Y centrality, respectively. The utilize of Roman numerals to designate quadrants avoids confusion, since Arabic numerals are used for the actual data represented in the graph.

In armed services unit designation, Roman numerals are often used to distinguish between units at different levels. This reduces possible defoliation, especially when viewing operational or strategic level maps. In item, army corps are often numbered using Roman numerals (for example the American Xviii Airborne Corps or the WW2-era German Iii Panzerkorps) with Arabic numerals being used for divisions and armies.

In music, Roman numerals are used in several contexts:

- Movements are often numbered using Roman numerals.

- In Roman Numeral Assay, harmonic role is identified using Roman Numerals.

- Individual strings of stringed instruments, such every bit the violin, are frequently denoted by Roman numerals, with higher numbers denoting lower strings.

In pharmacy, Roman numerals were used with the now largely obsolete apothecaries' system of measurement: including SS to denote "i one-half" and N to denote "aught".[45] [66]

In photography, Roman numerals (with nada) are used to announce varying levels of effulgence when using the Zone System.

In seismology, Roman numerals are used to designate degrees of the Mercalli intensity scale of earthquakes.

In sport the squad containing the "elevation" players and representing a nation or province, a club or a school at the highest level in (say) rugby union is frequently chosen the "1st XV", while a lower-ranking cricket or American football squad might exist the "3rd XI".

In tarot, Roman numerals (with null) are used to denote the cards of the Major Arcana.

In theology and biblical scholarship, the Septuagint is frequently referred to equally LXX, equally this translation of the Onetime Attestation into Greek is named for the legendary number of its translators (septuaginta being Latin for "seventy").

Modern use in European languages other than English

Some uses that are rare or never seen in English speaking countries may be relatively common in parts of continental Europe and in other regions (e.g. Latin America) that utilize a European language other than English. For instance:

Capital or small capital Roman numerals are widely used in Romance languages to denote centuries, due east.chiliad. the French XVIII e siècle [67] and the Castilian siglo Eighteen mean "18th century". Slavic languages in and adjacent to Russia similarly favor Roman numerals ( xviii век ). On the other hand, in Slavic languages in Central Europe, similar near Germanic languages, ane writes "18." (with a menses) before the local discussion for "century".

Boris Yeltsin's signature, dated x November 1988, rendered equally x.

Xi.'88.

Mixed Roman and Arabic numerals are sometimes used in numeric representations of dates (especially in formal messages and official documents, but also on tombstones). The calendar month is written in Roman numerals, while the day is in Standard arabic numerals: "4.6.1789" and "VI.iv.1789" both refer unambiguously to 4 June 1789.

Business hours table on a store window in Vilnius, Republic of lithuania.

Roman numerals are sometimes used to stand for the days of the week in hours-of-operation signs displayed in windows or on doors of businesses,[68] and too sometimes in railway and bus timetables. Mon, taken as the first day of the calendar week, is represented past I. Sunday is represented past Seven. The hours of operation signs are tables composed of two columns where the left column is the solar day of the week in Roman numerals and the right column is a range of hours of operation from starting time to closing time. In the instance case (left), the business opens from 10 AM to seven PM on weekdays, 10 AM to v PM on Saturdays and is closed on Sundays. Annotation that the listing uses 24-hour time.

Sign at 17.9 km on road SS4 Salaria, north of Rome, Italy.

Roman numerals may also be used for floor numbering.[69] [70] For example, apartments in primal Amsterdam are indicated as 138-3, with both an Standard arabic numeral (number of the block or firm) and a Roman numeral (floor number). The flat on the footing floor is indicated as 138-huis .

In Italian republic, where roads exterior built-upwardly areas accept kilometre signs, major roads and motorways also marking 100-metre subdivisionals, using Roman numerals from I to Ix for the smaller intervals. The sign IX / 17 thus marks 17.9 km.

Certain romance-speaking countries use Roman numerals to designate assemblies of their national legislatures. For instance, the composition of the Italian Parliament from 2018 to 2022 (elected in the 2018 Italian general election) is chosen the Xviii Legislature of the Italian Democracy (or more unremarkably the "Xviii Legislature").

A notable exception to the utilize of Roman numerals in Europe is in Greece, where Greek numerals (based on the Greek alphabet) are generally used in contexts where Roman numerals would be used elsewhere.

Unicode

The "Number Forms" block of the Unicode computer character fix standard has a number of Roman numeral symbols in the range of code points from U+2160 to U+2188.[71] This range includes both upper- and lowercase numerals, as well as pre-combined characters for numbers up to 12 (Ⅻ or XII). Ane justification for the existence of pre-combined numbers is to facilitate the setting of multiple-letter numbers (such every bit VIII) on a single horizontal line in Asian vertical text. The Unicode standard, however, includes special Roman numeral code points for compatibility just, stating that "[f]or most purposes, it is preferable to compose the Roman numerals from sequences of the appropriate Latin letters".[72] The cake also includes some apostrophus symbols for large numbers, an old variant of "L" (50) similar to the Etruscan character, the Claudian alphabetic character "reversed C", etc.

| Symbol | ↀ | ↁ | ↂ | ↅ | ↆ | ↇ | ↈ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 1,000 | 5,000 | x,000 | 6 | fifty | l,000 | 100,000 |

Run into also

- Biquinary

- Egyptian numerals

- Etruscan numerals

- Greek numerals

- Hebrew numerals

- Kharosthi numerals

- Maya numerals

- Roman abacus

- Proto-writing

- Roman numerals in Unicode

References

Notes

- ^ Without theorising well-nigh causation, information technology may be noted that Iv and IX not only accept fewer characters than IIII and VIIII, but are less likely to exist confused (especially at a quick glance) with III and Viii.

- ^ For numbers over 3,999 see large numbers

Citations

- ^ Alphabetic symbols for larger numbers, such every bit Q for 500,000, have also been used to various degrees of standardization. See Gordon, Arthur Due east. (1982). Illustrated Introduction to Latin Epigraphy. Berkeley: Academy of California Press. ISBN0-520-05079-seven.

- ^ Judkins, Maura (iv November 2011). "Public clocks practice a number on Roman numerals". The Washington Mail service . Retrieved 13 August 2019.

About clocks using Roman numerals traditionally utilize IIII instead of Four... 1 of the rare prominent clocks that uses the Iv instead of IIII is Big Ben in London.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (23 February 1990). "What is the proper way to style Roman numerals for the 1990s?". The Directly Dope.

- ^ a b Hayes, David P. "Guide to Roman Numerals". Copyright Registration and Renewal Information Chart and Web Site.

- ^ Reddy, Indra K.; Khan, Mansoor A. (2003). "1 (Working with Standard arabic and Roman numerals)". Essential Math and Calculations for Pharmacy Technicians. CRC Press. p. three. ISBN978-0-203-49534-six.

Table one-1 Roman and Standard arabic numerals (table very similar to the table hither, apart from inclusion of Vinculum notation.

- ^ Stanislas Dehaene (1997): The Number Sense : How the Mind Creates Mathematics. Oxford University Press; 288 pages. ISBN 9780199723096

- ^ Ûrij Vasilʹevič Prokhorov and Michiel Hazewinkel, editors (1990): Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, Volume 10, page 502. Springer; 546 pages. ISBN 9781556080050

- ^ Dela Cruz, M. 50. P.; Torres, H. D. (2009). Number Smart Quest for Mastery: Teacher's Edition. King Bookstore, Inc. ISBN9789712352164.

- ^ Martelli, Alex; Ascher, David (2002). Python Cookbook . O'Reilly Media Inc. ISBN978-0-596-00167-4.

- ^ a b Julius Caesar (52–49 BC): Commentarii de Bello Gallico. Book Ii, Section 4: "... Xv milia Atrebates, Ambianos 10 milia, Morinos XXV milia, Menapios VII milia, Caletos X milia, Veliocasses et Viromanduos totidem, Atuatucos XVIIII milia; ..." Section 8: "... ab utroque latere eius collis transversam fossam obduxit circiter passuum CCCC et advertizing extremas fossas castella constituit..." Volume IV, Section 15: "Nostri advertisement unum omnes incolumes, perpaucis vulneratis, ex tanti belli timore, cum hostium numerus capitum CCCCXXX milium fuisset, se in castra receperunt." Volume Vii, Section 4: "...in hiberna remissis ipse se recipit die XXXX Bibracte."

- ^ Angelo Rocca (1612) De campanis commentarius. Published by Guillelmo Faciotti, Rome. Championship of a Plate: "Campana a XXIIII hominibus pulsata" ("Bell to be sounded past 24 men").

- ^ Gerard Ter Borch (1673): Portrait of Cornelis de Graef. Date on painting: "Out. XXIIII Jaer. // M. DC. LXXIIII".

- ^ Pliny the Elder (77–79 Advertizement): Naturalis Historia, Book 3: "Saturni vocatur, Caesaream Mauretaniae urbem CCLXXXXVII p[assum]. traiectus. reliqua in ora flumen Tader ... ortus in Cantabris haut procul oppido Iuliobrica, per CCCCL p. fluens ..." Book 4: "Epiri, Achaiae, Atticae, Thessalia in porrectum longitudo CCCCLXXXX traditur, latitudo CCLXXXXVII." Book Six: "tam vicinum Arsaniae fluere eum in regione Arrhene Claudius Caesar auctor est, ut, cum intumuere, confluant nec tamen misceantur leviorque Arsanias innatet MMMM ferme spatio, mox divisus in Euphraten mergatur."

- ^ Thomas Bennet (1731): Grammatica Hebræa, cum uberrima praxi in usum tironum ... Editio tertia. Published by T. Astley, copy in the British Library; 149 pages. Page 24: "PRÆFIXA duo sunt viz. He emphaticum vel relativum (de quo Cap 6 Reg. LXXXX.) & Shin cum Segal sequente Dagesh, quod denotat pronomen relativum..."

- ^ Pico Della Mirandola (1486) Conclusiones sive Theses DCCCC ("Conclusions, or 900 Theses").

- ^ "360:12 tables, 24 chairs, and plenty of chalk". Roman Numerals...not quite so elementary. 2 January 2011.

- ^ "Paul Lewis". Roman Numerals...How they work. thirteen Nov 2021.

- ^ Milham, Due west.I. (1947). Time & Timekeepers. New York: Macmillan. p. 196.

- ^ a b Pickover, Clifford A. (2003). Wonders of Numbers: Adventures in Mathematics, Mind, and Pregnant. Oxford University Press. p. 282. ISBN978-0-19-534800-ii.

- ^ Adams, Cecil; Zotti, Ed (1988). More of the straight dope. Ballantine Books. p. 154. ISBN978-0-345-35145-6.

- ^ a b c Asimov, Isaac (1966). Asimov on Numbers (PDF). Pocket Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 12.

- ^ "Gallery: Museum's North Archway (1910)". Saint Louis Art Museum. Archived from the original on 4 Dec 2010. Retrieved ten January 2014.

The inscription over the North Entrance to the Museum reads: "Defended to Fine art and Free to All MDCDIII." These roman numerals translate to 1903, indicating that the engraving was part of the original building designed for the 1904 World's Fair.

- ^ Reynolds, Joyce Maire; Spawforth, Anthony J. Southward. (1996). "numbers, Roman". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Anthony (eds.). Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Printing. ISBN0-19-866172-10.

- ^ Kennedy, Benjamin Hall (1923). The Revised Latin Primer. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- ^ "ROMAN function". back up.microsoft.com.

- ^ Michaele Gasp. Lvndorphio (1621): Acta publica inter invictissimos gloriosissimosque&c. ... et Ferdinandum II. Romanorum Imperatores.... Printed past Ian-Friderici Weissii. Page 123: "Sub Dato Pragæ IIIXX Decemb. A. C. M. DC. IIXX". Page 126, stop of the same document: "Dabantur Pragæ 17 Decemb. M. DC. IIXX".

- ^ Raphael Sulpicius à Munscrod (1621): Vera Ac Germana Detecto Clandestinarvm Deliberationvm. Page 16, line ane: "repertum Originale Subdatum IIIXXX Aug. A. C. MDC.IIXX". Page 41, upper correct corner: "Decemb. A. C. MDC.IIXX". Page 42, upper left corner: "Febr. A. C. MDC.19". Page seventy: "IIXX. dice Maij sequentia in consilio noua ex Bohemia allata....". Page 71: "19. Maij".

- ^ Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel (1699): Als Ihre Königl. Majestät in Pohlen und .... Page 39: "... und der Umschrifft: Lithuania ASSERTA M. DC. IIIC [1699]."

- ^ Joh. Caspar Posner (1698): Mvndvs ante mvndvm sive De Chao Orbis Primordio, title folio: "Ad diem jvlii A. O. R. M DC IIC".

- ^ Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel (1700): Saxonia Nvmismatica: Das ist: Die Historie Des Durchlauchtigsten.... Page 26: "Die Revers lid eine feine Inscription: SERENISSIMO DN.DN... SENATUS.QVERNF. A. M DC IIC D. 18 Oct [year 1698 twenty-four hours 18 oct]."

- ^ Enea Silvio Piccolomini (1698): Opera Geographica et Historica. Helmstadt, J. M. Sustermann. Title page of first edition: "Bibliopolæ ibid. M DC IC".

- ^ Kennedy, Benjamin H. (1879). Latin grammar. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 150. ISBN9781177808293.

- ^ Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy A (2004). Handbook to life in ancient Rome (2 ed.). p. 270. ISBN0-8160-5026-0.

- ^ Boyne, William (1968). A transmission of Roman coins. p. thirteen.

- ^ Degrassi, Atilius, ed. (1963). Inscriptiones Italiae. Vol. 13: Fasti et Elogia. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato. Fasciculus 2: Fasti anni Numani et Iuliani.

- ^ a b Stephen James Malone, (2005) Legio 20 Valeria Victrix.... PhD thesis. On folio 396 information technology discusses many coins with "Leg. IIXX" and notes that it must be Legion 22. The footnote on that folio says: "The form IIXX conspicuously reflecting the Latin duo et vicensima 'twenty-second': cf. X5398, legatus I[eg II] I et vicensim(ae) Pri[mi]chiliad; Six 1551, legatus leg] IIXX Prj; 3 14207.7, miles leg IIXX; and Three 10471-3, a vexillation fatigued from iv German legions including '18 PR' – surely hither the stonecutter's hypercorrection for IIXX PR.

- ^ 50' Atre périlleux et Yvain, le chevalier au lion . 1301–1350.

- ^ a b M. Gachard (1862): "Two. Analectes historiques, neuvième série (nos CCLXI-CCLXXXIV)". Bulletin de la Commission royale d'Historie, volume iii, pages 345–554. Page 347: Lettre de Philippe le Beau aux échevins..., quote: "Escript en nostre ville de Gand, le XXIIIIme de febvrier, fifty'an IIIIXX19 [quatre-vingt-dix-neuf = 99]." Folio 356: Lettre de l'achiduchesse Marguerite au conseil de Brabant..., quote: "... Escript à Bruxelles, le dernier jour de juing anno XVcXIX [1519]." Folio 374: Letters patentes de la rémission ... de la ville de Bruxelles, quote: "... Op heden, tweentwintich ['twenty-ii'] daegen in decembri, anno vyfthien hondert tweendertich ['fifteen hundred thirty-two'] ... Gegeven op x vyfsten dach in deser jegewoirdige maent van decembri anno XV tweendertich [1532] vorschreven." Page 419: Acte du duc de Parme portant beatitude..., quote": "Faiet le Fifteenme de juillet XVc huytante-six [1586]." doi:10.3406/bcrh.1862.3033.

- ^ Herbert Edward Salter (1923) Registrum Annalium Collegii Mertonensis 1483–1521 Oxford Historical Society, volume 76; 544 pages. Page 184 has the ciphering in pounds:shillings:pence (li:s:d) x:iii:iiii + xxi:eight:eight + xlv:xiiii:i = iii20xvii:vi:i, i.e. x:three:4 + 21:8:8 + 45:14:i = 77:vi:one.

- ^ Johannis de Sancto Justo (1301): "E Duo Codicibus Ceratis" ("From Two Texts in Wax"). In de Wailly, Delisle (1865): Contenant la deuxieme livraison des monumens des regnes de saint Louis,... Volume 22 of Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France. Page 530: "SUMMA totalis, Thirteen. M. V. C. III. XX. XIII. fifty. III s. 11 d. [Sum full, 13 thousand 5 hundred three score thirteen livres, 3 sous, 11 deniers].

- ^ "Our Brand Story". SPC Ardmona. Retrieved xi March 2014.

- ^ Faith Wallis, trans. Bede: The Reckoning of Time (725), Liverpool, Liverpool Univ. Pr., 2004. ISBN 0-85323-693-3.

- ^ Byrhtferth'southward Enchiridion (1016). Edited by Peter South. Baker and Michael Lapidge. Early English language Text Society 1995. ISBN 978-0-19-722416-8.

- ^ C. Westward. Jones, ed., Opera Didascalica, vol. 123C in Corpus Christianorum, Serial Latina.

- ^ a b c Bachenheimer, Bonnie South. (2010). Manual for Pharmacy Technicians. ISBN978-1-58528-307-1.

- ^ "RIB 2208. Altitude Slab of the 6th Legion". Roman Inscriptions in Britain . Retrieved eleven November 2020.

- ^ Maher, David Due west.; Makowski, John F., "Literary Testify for Roman Arithmetic with Fractions Archived 27 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine", Classical Philology 96 (2011): 376–399.

- ^ "Merriam-Webster Unabridged Lexicon".

- ^ a b c d Perry, David J. Proposal to Add Additional Ancient Roman Characters to UCS Archived 22 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Ifrah, Georges (2000). The Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to the Invention of the Computer. Translated by David Bellos, Due east. F. Harding, Sophie Wood, Ian Monk. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Chrisomalis, Stephen (2010). Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge Academy Press. pp. 102–109. ISBN978-0-521-87818-0.

- ^ Gordon, Arthur Due east. (1982). Illustrated Introduction to Latin Epigraphy. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 122–123. ISBN0-520-05079-7.

- ^ "RIB 2208. Distance Slab of the Twentieth Legion". Roman Inscriptions in U.k. . Retrieved nine November 2020.

- ^ Chrisomalis, Stephen (2010). Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge Academy Press. p. 119. ISBN978-0-521-87818-0.

- ^ "What is Vinculum Notation?". Numerals Converter. four March 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "RIB 2171. Building Inscription of the Second and Twentieth Legions". Roman Inscriptions in Uk . Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ a b Gilles Van Heems (2009)> "Nombre, chiffre, lettre : Formes et réformes. Des notations chiffrées de l'étrusque" ("Betwixt Numbers and Letters: Virtually Etruscan Notations of Numeral Sequences"). Revue de philologie, de littérature et d'histoire anciennes, volume LXXXIII (83), effect 1, pages 103–130. ISSN 0035-1652.

- ^ Keyser, Paul (1988). "The Origin of the Latin Numerals 1 to 1000". American Journal of Archaeology. 92 (4): 529–546. doi:10.2307/505248. JSTOR 505248. S2CID 193086234.

- ^ Hopkins, Keith (2005). The Colosseum. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Academy Press. ISBN978-0-674-01895-2.

- ^ Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (First ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-xix-288003-i.

- ^ Bastedo, Walter A. Materia Medica: Pharmacology, Therapeutics and Prescription Writing for Students and Practitioners, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia, PA: West.B. Saunders, 1919) p582. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ^ Capelli, A. Dictionary of Latin Abbreviations. 1912.

- ^ Bang, Jørgen. Fremmedordbog, Berlingske Ordbøger, 1962 (Danish)

- ^ Gordon, Arthur E. (1983). Illustrated Introduction to Latin Epigraphy . Academy of California Press. p. 44. ISBN9780520038981 . Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ NFL won't use Roman numerals for Super Bowl fifty Archived 1 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, National Football League. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ Reddy, Indra K.; Khan, Mansoor A. (2003). Essential Math and Calculations for Pharmacy Technicians. CRC Press. ISBN978-0-203-49534-six.

- ^ Lexique des règles typographiques en usage à l'imprimerie nationale (in French) (sixth ed.). Paris: Imprimerie nationale. March 2011. p. 126. ISBN978-2-7433-0482-ix. On composera en chiffres romains petites capitales les nombres concernant : ↲ 1. Les siècles.

- ^ Beginners latin Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Automobile, Government of the Uk. Retrieved i December 2013.

- ^ Roman Arithmetic Archived 22 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Southwestern Adventist Academy. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Roman Numerals History Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Auto. Retrieved 1 Dec 2013.

- ^ "Unicode Number Forms" (PDF).

- ^ "The Unicode Standard, Version half-dozen.0 – Electronic edition" (PDF). Unicode, Inc. 2011. p. 486.

Sources

- Menninger, Karl (1992). Number Words and Number Symbols: A Cultural History of Numbers. Dover Publications. ISBN978-0-486-27096-8.

Further reading

- Aczel, Amir D. 2015. Finding Zilch: A Mathematician'due south Odyssey to Uncover the Origins of Numbers. 1st edition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Goines, David Lance. A Constructed Roman Alphabet: A Geometric Assay of the Greek and Roman Capitals and of the Arabic Numerals. Boston: D.R. Godine, 1982.

- Houston, Stephen D. 2012. The Shape of Script: How and Why Writing Systems Modify. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Inquiry Press.

- Taisbak, Christian M. 1965. "Roman numerals and the abacus." Classica et medievalia 26: 147–60.

External links

- "Roman Numerals (Totally Epic Guide)". Know The Romans.

Periodic Table With Roman Numerals,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_numerals

Posted by: thayerwitify.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Periodic Table With Roman Numerals"

Post a Comment